Every page spread introduces a new theory concept — such as intervals, note reading, or rests — and presents it through a unique, creative approach using storytelling, visual metaphors, physical activities and child-friendly humor.

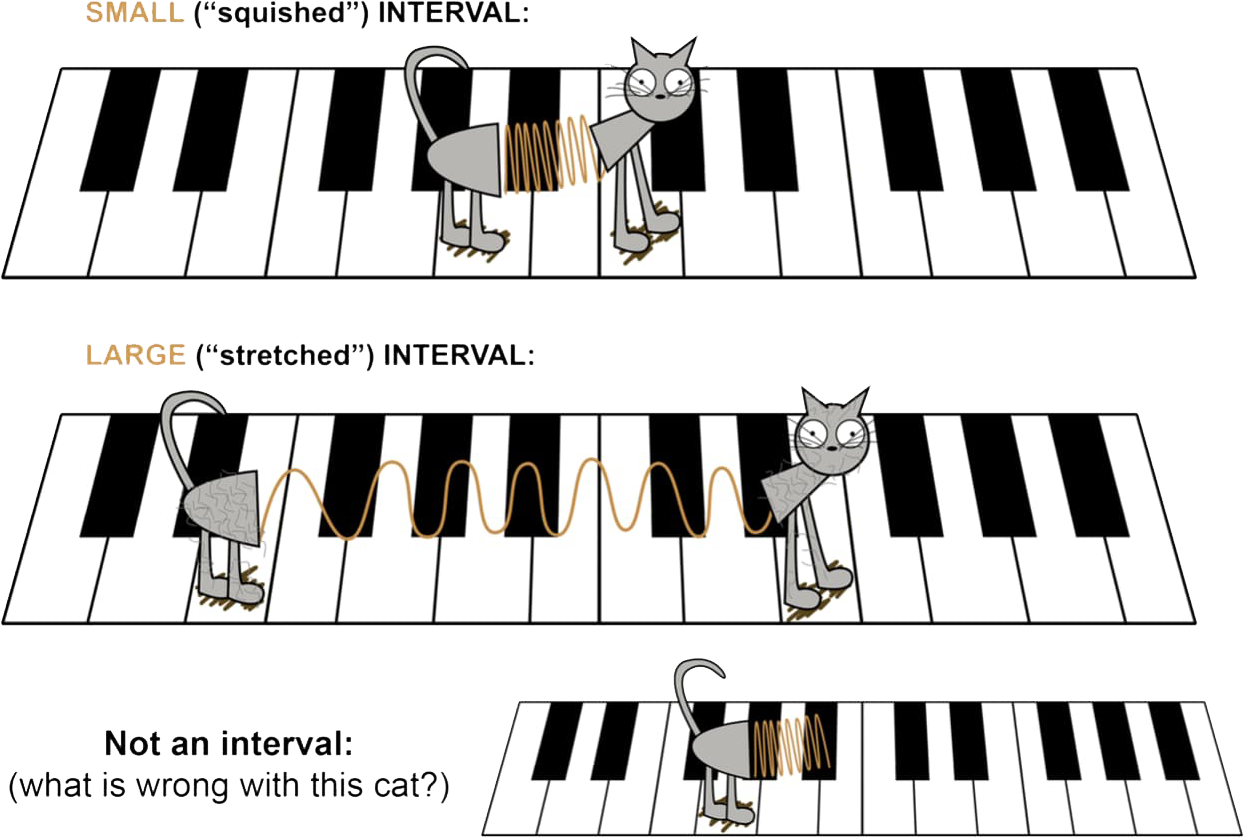

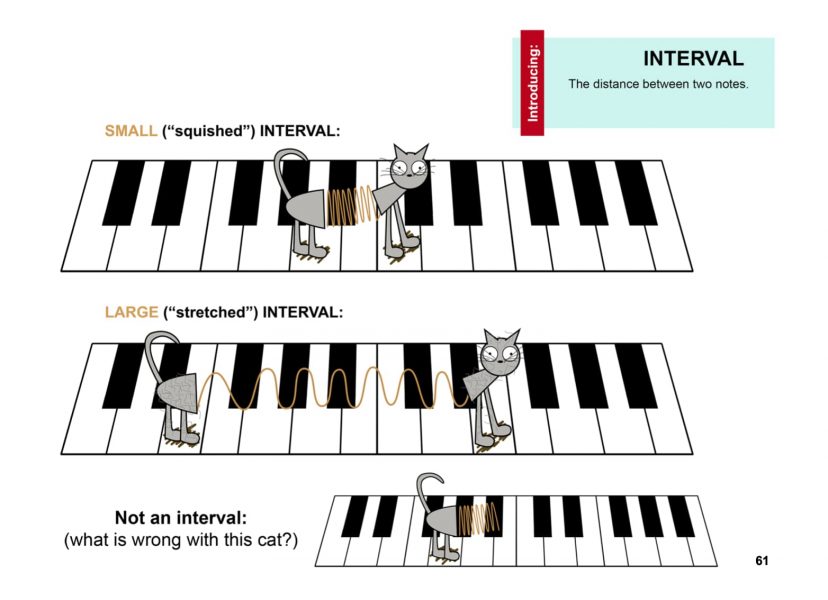

Whether it’s a slinky cat explaining intervals…

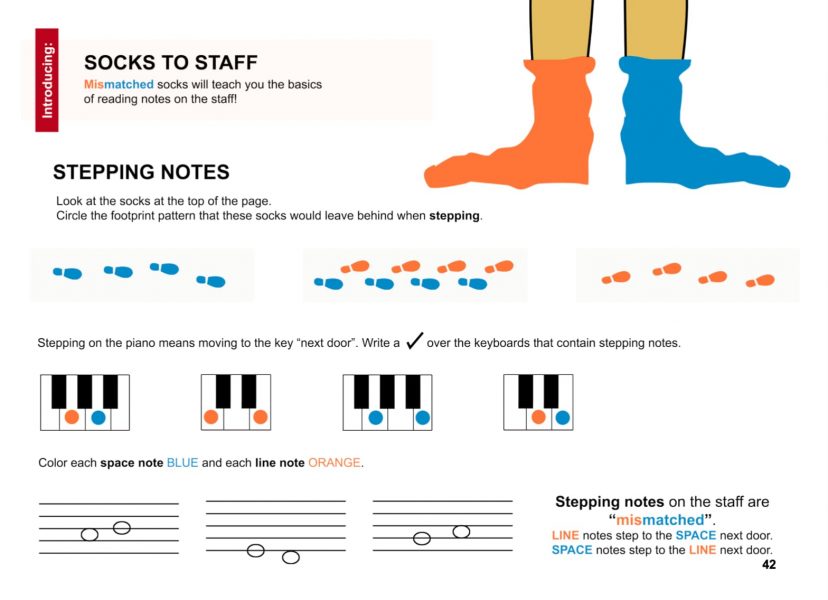

…students wearing mismatched socks to teach steps and skips…

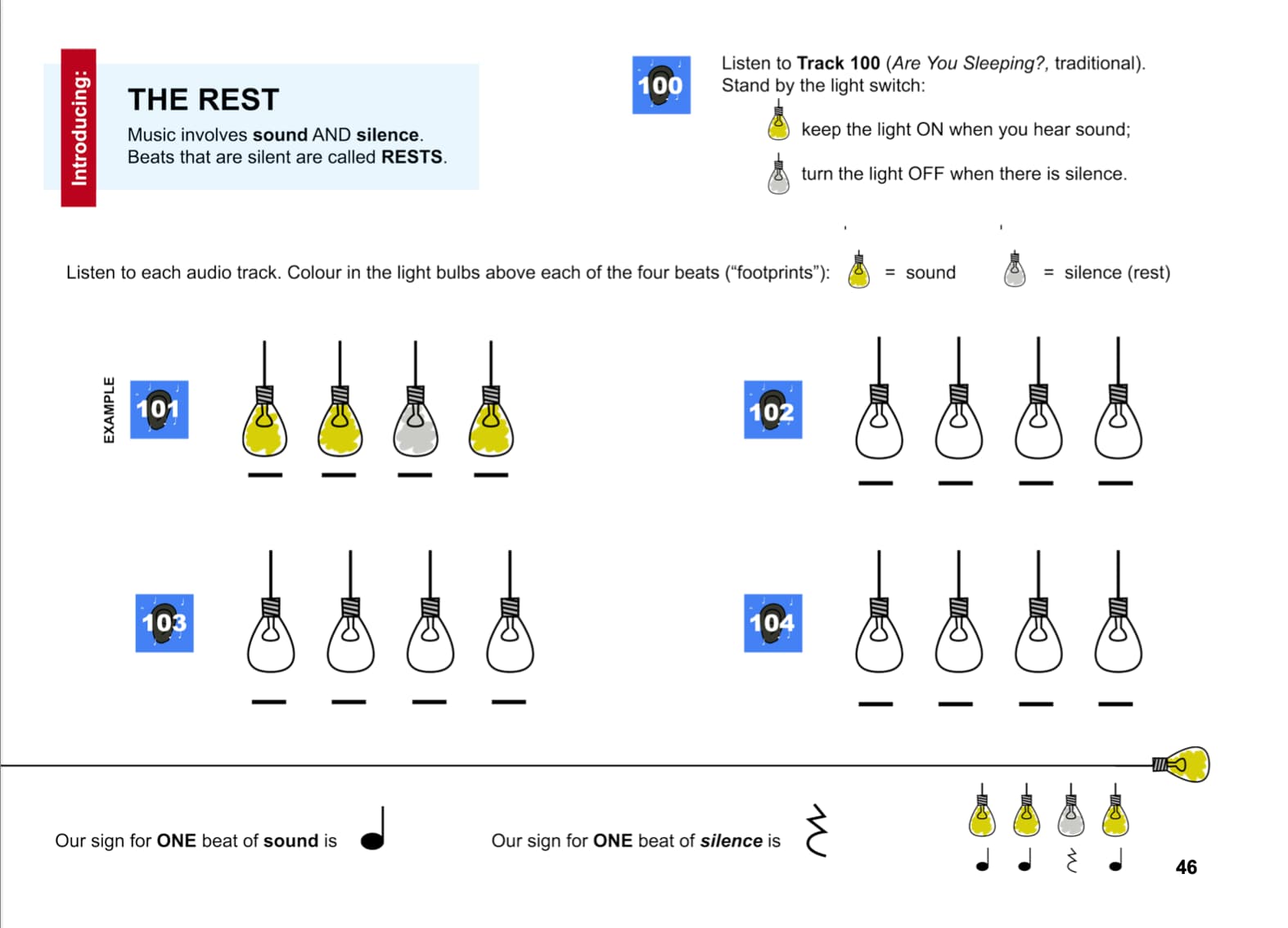

…or students turning light switches off and on to understand rhythm…

…the book transforms theory into something kids actually look forward to.

And the best part is, all the materials required are everyday items you already have at home.

Interview of Amy Dalziel

My musical journey began when I was turning six years old—which I think is a pretty common age to start learning piano. I have a lot of older siblings, and they all played piano too, so I was super motivated to learn when I reached that age. I just really took to it—I loved it. I had a great teacher and stayed with her throughout my entire childhood.

When I reached Grade 12, I switched to a different teacher as I was preparing for university auditions. My original teacher felt it would be helpful to get another perspective, and she was right.

From there, I pursued an undergraduate degree in general music, but my focus was very much on piano performance.

After that, I began a two-year master’s degree in Piano Performance & Pedagogy.

My first year was in Edmonton, where I had the opportunity to observe their large Suzuki program. That experience really opened my eyes.

Up until that point, my musical training had been very focused on notation and developing strong reading skills. Suzuki, in contrast, emphasized learning by rote and ear, and that got me thinking: What if I rethought how I wanted to teach piano?

A lot of the ideas came to me over the course of more than ten years of teaching. I’ve always loved trying new things—I find it exciting to question whether we’re doing something the best way we can, or whether there might be a better, more engaging approach. So I was constantly experimenting with how I taught, and some of those experiments turned into great ideas… and some of them were total flops!

I also happen to have a cat, so there are a lot of cats in the book—she’s even listed as the co-author on the last page. That personal connection helped spark ideas too. I found myself thinking, “What are kids interested in?” For example, a lot of them know Toy Story, so when I introduced the idea of a slinky cat—based on the slinky dog from the movie—it really resonated with them. They were excited because it was something familiar.

That kind of recognition is empowering for students. They already understand the reference before I even start teaching the concept. It makes the lesson more engaging and helps them connect with the material right away. And I turned the slinky dog into a cat because—well, I like cats!

I think my book actually covers the same core content as many of the popular theory books teachers are already using. It includes the fundamentals—things like rests, steps and skips (which I call “hops”), notes on the piano, high and low sounds—all the essential building blocks.

What’s different is the approach. It’s presented in a more playful and creative way, which I think makes it more engaging for students.

One reason I included over 130 audio tracks was to support teachers who might feel unsure about how to deliver certain activities. If something in the book isn’t immediately clear, they can listen to a track and hear exactly what I’m trying to do. It helps take out the guesswork.

Some teachers might worry that switching to a different method will be too much work, but I’ve tried to make the book as user-friendly as possible. In fact, some activities are even easier to run with the tracks because it frees up the teacher to join in and model alongside the student.

So yes, it’s different—but it’s not harder. It just brings a bit more playfulness into the process, while keeping the same educational goals.

One of the earliest inspirations came from a lesson with a five-year-old student. We had been doing some off-the-bench games about high and low sounds, and when we came back to the piano, I asked her to find the “high notes.” She paused and then looked straight up at the ceiling.

It was such a sweet moment—and also incredibly insightful. Of course she looked up! To a child, “high” naturally means “up in the air,” not “to the right on the keyboard.” That small misunderstanding really stuck with me. It made me realize how abstract our musical language can be for young learners.

So, I came up with the idea of a fallen tree. I imagined the tree cut down, with the trunk lying behind the low keys and the branches stretching out behind the high keys. I even made paper cutouts and taped them behind the piano to visually reinforce the concept. From then on, we played “music detectives,” looking for the trunk and branches as clues to find the high and low notes.

That simple moment—watching her look up—really shaped how I teach spatial concepts in music. And it reminded me how much we can learn from our students when we slow down and see the world from their perspective.

Yes, I think those aha moments are at the heart of really effective teaching. I’ve always been interested in how to teach in a way that’s not just clear, but genuinely memorable. I noticed early on that with younger students, some concepts—especially theoretical ones—just weren’t clicking. It wasn’t that the students weren’t capable, it’s that the way I was presenting the information wasn’t resonating with how they think and learn.

So I started playing around with ideas. For example, when we were learning about steps and skips, I came up with the idea of “mismatched socks.” I had students wear different-colored socks to class and we’d play games involving stepping in patterns—orange, blue, orange, blue. When someone tried to step with two orange socks in a row, we noticed they weren’t stepping anymore—they were hopping. That led us straight into a visual and physical understanding of music steps versus skips.

Then we’d transfer that to the staff, coloring all the spaces one color and the lines another. That’s when it clicked. They suddenly saw, “Oh! That’s a step—space to line or line to space!” That moment of recognition, that excitement when they get it on their own—that’s what I’m always aiming for. It’s fun, it’s memorable, and it sticks.

So my piano website is www.pianoseeds.com. There are two main sections on the site.

The first is all about curriculum packages—these are designed to help teachers introduce key musical concepts in creative, playful ways. It’s not just about practicing something a student already knows; it’s about creating those aha! moments—where the learning really clicks. For example, how do we actually teach the idea of high and low? Or steady beat? Or up and down? Each package focuses on a specific concept and includes 5 to 10 activities—movement, listening, games—and comes with all the printable materials you’ll need. You just download a PDF, and it’s all there.

The second section is focused on my book, Music Theory Inside Out. All the audio tracks that go along with the book—there are about 140 of them—are free to download. You can grab them all at once or in smaller sets. There are also a few sample pages so you can get a feel for what the book is like.

These curriculum packs are separate from the book, but they definitely echo the same ideas. For instance, both use creative visuals like the “tree that’s fallen down” to teach musical direction. The big difference is that the curriculum packages are packed with more hands-on games and activities—things that wouldn’t really fit into a printed theory book. And yes, they’re all completely free to download.